It has been a busy start to 2022 and I had decided to spend most weekend this month at home – Psst, I am in favour of a warm bed and peace over a good book or a nice movie as opposed to a restaurant vibrating with high-decibel blathers and drizzling with natters!

As I was occupied with work commitment during the week, I’d try to finish a book that I picked up over Christmas and watch some movies – old and new. I came across a movie called “The Big Short” last weekend, thanks to an online streaming service. It was based on a non-fiction book by Michael Lewis, about the real lives of several people in the financial industry during the mid-2000s against the backdrop of the rise and then dramatic collapse of the US real estate market that eventually led to global financial crisis in 2008.

The 2008 financial crisis began as a subprime mortgage crisis. Mortgage lending is an important part of a bank’s balance sheets. Banks lend money to would-be homeowners, and they pay this money back with interest, in regular installments that show up as reliable profit for the bank. Mortgages are among the safest loans a bank can make, because the homeowners put up their house as collateral. Borrowers want to keep their homes, so they do their best to make payments. And if a borrower does default, the bank comes into possession of the house.

For the bank, historically, this has been win-win. This however changed during the early 2000s. Mortgage lenders began offering bigger and bigger loans to more and more borrowers, including people who did not have the income to service these loans. Since mortgages are collateralised and deemed low-risk, banks began bundling up large sets of mortgages into something called a “mortgage-backed security”, which then sold to investors with the assurance that they were safe and profitable. Banks created all sorts of investment products – not just bundles of mortgages, but bundles of those bundles, and bundles of those bundles – premised on the underlying bet that the housing market would continue to rise. Most of the world’s biggest investment houses, including pension funds, were tied up in these bets. Unfortunately, the bet was lost. By 2007, subprime borrowers were defaulting on their mortgage in growing numbers, and when the banks foreclosed on these houses, this flooded the market and depressed housing prices. This also created a problem for anyone holding a mortgage-backed security. Investment banks and insurance houses discovered that their balance sheets were full of unsellable assets with no practical value. Almost overnight, every major financial institution found itself in a liquidity crisis, and some eventually were bailed out. Banks had to take a haircut and their behaviour shifted. To them, ‘innovation’ and experimental financial instruments had gotten the banks into trouble in the first place, and they steered clear of anything that seemed remotely innovative.

Photo: AP

After watching “The Big Short,” I could not help but reflect: Wall Street banks, as a result of the financial shock, were focused on themselves and began to turn inward whereas Silicon Valley during that exact time had seen the birth of iPhone – dubbed the first-gen of smartphone (Steve Jobs’ famous keynote “today Apple is going to reinvent the phone”) – and started to explore ways that emerging technologies might appeal to everyday consumers. Eight days before the collapse of Bear Stearns, Apple released a software development kit that offered developer community a legitimate way to write software for the iPhone. And a day before the US FDIC seized the mortgage company IndyMac, Apple launched its App Store – a way for those developers to distribute their software to iPhone users worldwide. The launch of App Store led from no apps to hundreds of apps overnight: the modern mobile computing platform is born!

iPhone does not just reinvent the phone. It has remade an entire industry – Fintech – and started a financial revolution.

The improvements of mobile computing have fundamentally reshaped and digitised the ways we interact with our money. Platforms like PayPal, eGHL and iPay88 have made it easier than ever to shop. Banking APIs such as those provided by Finology allow us to move money seamlessly between our accounts, and personal finance managers like Pod mean that we can see what goes into and out of those accounts with ease. When we are short on money, online lenders like Funding Societies can transfer money into our bank within days if not hours. And online investment tools like Versa give us simple and efficient ways of growing the money in our accounts over time.

Fintech has de-bundled the banks, converting the banking products into customer-friendly apps that each provide just one service, but better. Along the way, Fintech has opened financial services to more people than ever.

But, in order to enjoy these services, Fintech’s customers still require banks: online payment is quick if you have a debit or credit card; a digital loan is fast if there is a bank to receive the loan; as mobile app doesn’t accept cash, growing savings through online tools is only possible if you have a bank account.

These Fintech apps require their users to link their accounts, at some point or another, to a bank.

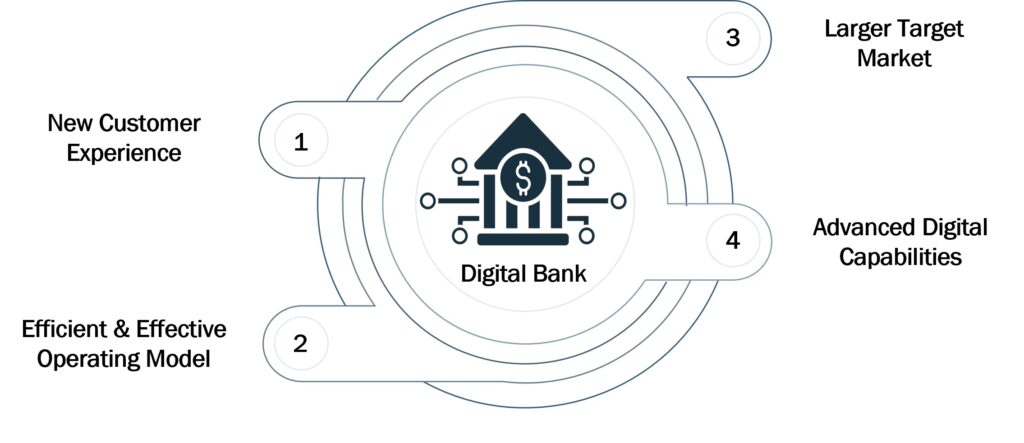

The award of digital bank licenses by Bank Negara Malaysia, slated in the first quarter of this year, is a gamechanger for Fintech in Malaysia. Traditional physical branch networks are no longer necessary and the services of these “neobanks” or “challenger banks” would be entirely accessed by customers through internet or virtually. The formation of these mobile or neobanks would steer the financial services industry towards “Banking-as-a-Service” (BaaS), where the brand and the service can be distinguished from one another. Banking services in Malaysia and in this fast-growing region could one day be offered through an abstraction layer and delivered to any brand. What Bill Gates once said in 1994 is near coming true: “banking is necessary, banks are not”.

The banking industry is one of the oldest industries known to man, even predating the Roman Empire when merchants started making grain loans to farmers and traders while carrying goods between cities within the areas of Assyria and Babylonia back in 2000BC. The industry then saw rapid development as it went through different civilisations throughout time and had created the foundations of modern banking – it is believed that deposits, loans and currency exchange were already adopted by ancient Greece!

Fast forward to today, the banking industry as we know it had weathered multiple economic downturns, globalisation and rapid technological advancements to adapt to modern society. Developments in telecommunications and computing during the 20th century, for instance, had allowed the bigger banks to dramatically cast a wider net and serve consumers from all over the world. Banking has had to acclimatise itself in various ways such as by offering more products and services via digital channels to cater to present-day demands, and the next big thing to happen to it might just be around the corner.

Digital Banking

With the rapid technological advancements seen over the past decade or so together with its mass adoption, we could potentially see further disruption to the current banking model in the form of digital banking. From the demand perspective, digital banking makes perfect sense. It aims to leverage on high technological adoption and digitalisation efforts to provide greater financial inclusion by offering products and services to address market gaps in the underserved and unserved segments e.g., rural residents and gig workers. It does this by leveraging innovative application of technology and a wider set of data which includes spending habits to determine credit scores. As these consumers typically lack the credit history and in turn have low access to financial services, digital banking solves this demand-supply gap while eliminating the need for traditional brick-and-mortar bank branches typically seen today.

According to a study by Google, Temasek, and Bain in 2019, 40% of Malaysian adults were underbanked, meaning they had underserved financial service needs, while 15% did not have a bank account. As five digital banking licenses are set to be awarded and announced sometime in the First Quarter of 2022, Malaysia stands to reap the benefits of digital banking and could see a shift in consumer behaviour.

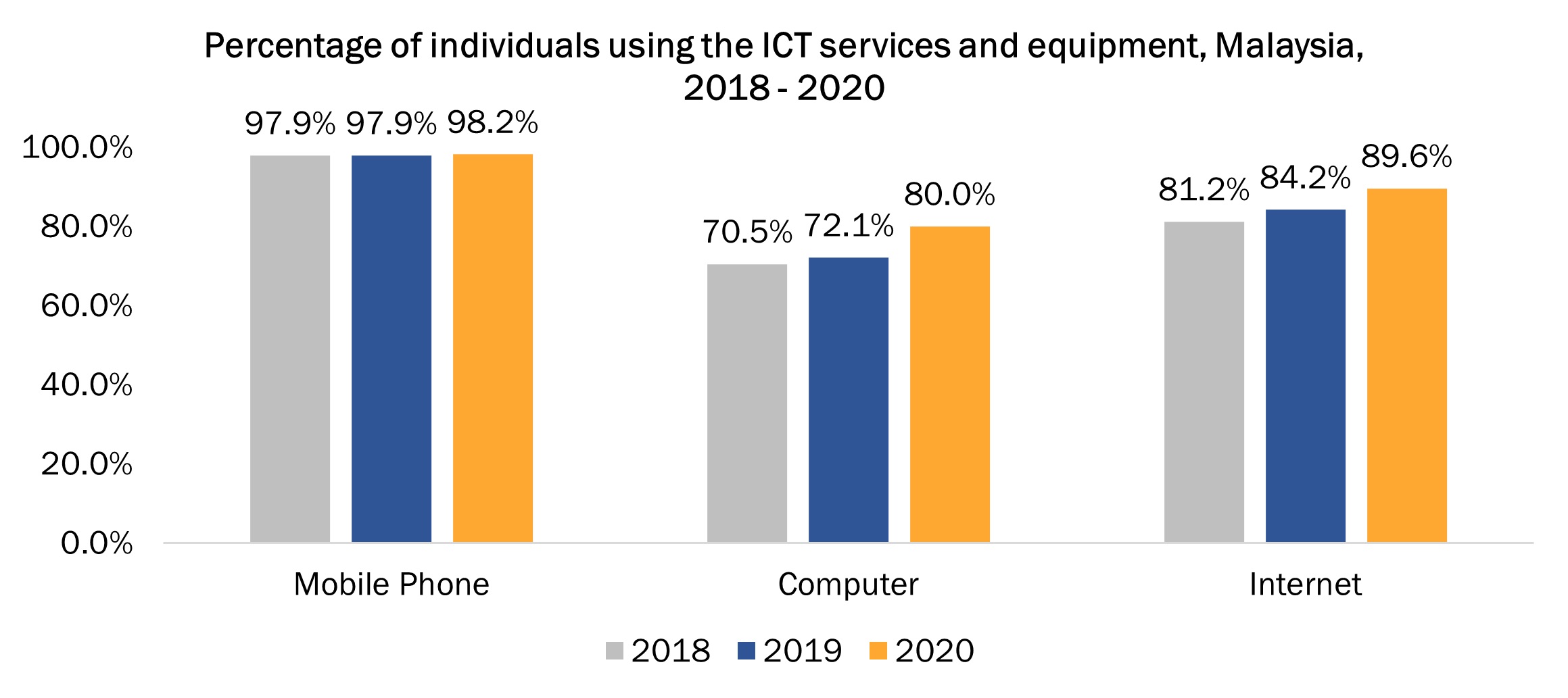

As far as adoption is concerned, Malaysia has seen strong traction when it comes to the usage of technology and internet which sets up for a conducive environment for digital banking to penetrate the masses. Besides, Malaysians are already accustomed to online banking – a service not too dissimilar to digital banking – especially coming off the pandemic which has augmented digitalisation efforts and technological adoption in the financial sector.

Addressing the Pain Points

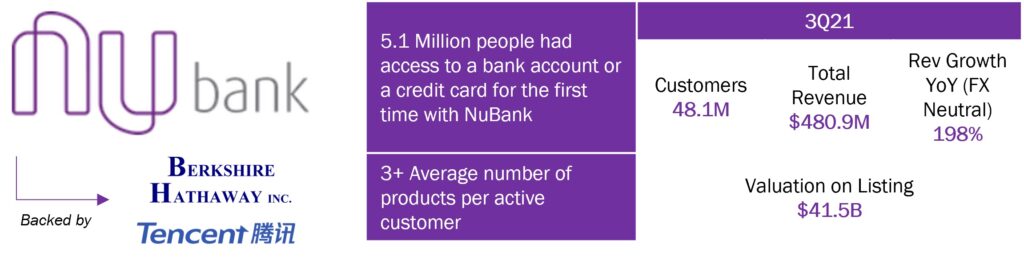

Even if we look beyond the Malaysian context, digital banking is proven able to address certain pain points unique to their target markets. Take Brazilian digital bank Nubank as an example. Nubank was launched in 2013 in a country where only five banks were controlling over 80% of the country’s assets. This concentration in market share resulted in high fees (annual credit card interest rates could run as high as 300%) and a serious underbanked population (bank branches were only found in 60% of Brazil’s cities which resulted a third of the Brazilian population unbanked). As such, CEO David Vélez sought to address these problems and co-founded Nubank which provided a low-cost, convenient alternative to traditional banks.

Nubank had garnered massive success by offering services at zero fees and low interest rates all at the convenience of a smartphone. Less than 10 years after its birth, it has survived a recession and a pandemic, gained over 48 million customers across Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico and fetched a valuation higher than other Fintech players such as Chime, Robinhood and SoFi. Its disruptive solutions enabled the company to obtain backing from the likes of Warren Buffett, Tencent, Invesco and Sequoia. Nubank recently went public on the New York Stock Exchange at a valuation close to $42 billion, making it one of 2021’s largest IPOs.

Fintech and Traditional Banks – A Match Made in Heaven

Coming back to Malaysia, Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM) has stated that they will issue up to five licenses and successful applicants will be notified in the first quarter of 2022. It is reported that there are 29 consortiums bidding for the five digital banking licenses. With a myriad of applicants fighting for just a handful of licenses, the burning question that everyone is asking is: what is BNM looking for in their applicants in determining the winners?

Based on our research, BNM isn’t just looking to serve the underbanked and unbanked, but they are also taking a more holistic view on the whole banking ecosystem. Suhaimi Ali, Director of Financial Development and Innovation at BNM says that the central bank is looking to identify three types of Digital Banks among the applicants:

| 1. | Specialist | : | Targets a specific customer segment by tailoring product offerings |

| 2. | Ecosystem Players | : | Leverages on brands, channel footprint and pre-existing customer based on non-banking services |

| 3. | Innovative Basic Banking Providers | : | Offers simple products for everyday banking while using technology for in depth customer insights and hyper-personalisation |

It remains to be seen which applicants will fall in each of the abovementioned categories. Nonetheless, BNM has a diverse mix of applicants to choose from. A few notable consortiums among the 29 applicants are as follows:

It is interesting to note that among the consortiums vying for the digital banking license, there are a few financial institutions that have partnered with Fintech start-ups. An obvious example of this is the RHB-Axiata consortium. One could ask the question on the rationale behind a large traditional bank bidding for a digital license when they already have a banking license. According to RHB, they see the digital bank as an extension of its Digital Transformation Programme which is a core component of its FIT22 strategy. With the right digital model and partner, RHB seeks to increase financial inclusion and expedite the development of digital journeys and products to wider segments of the community (e.g., small enterprises, gig economy, etc). RHB will bring to the consortium many years of established trust with customers and regulators, as well as extensive experience in running a bank with proven expertise across core banking services, risk management and compliance, liquidity, capital, operational and credit management, product management, and responsible financing. On the other hand, Axiata via its subsidiary Boost will act as the technical partner in the consortium, providing intimate knowledge of customers via analytics and artificial intelligence gained through Aspirasi and the Boost e-Wallet.

On the surface, this looks like a match made in heaven – Axiata’s expertise in the Fintech space combined with RHB’s experience in the traditional, heavily-regulated banking space as well as their balance sheet size. Further, the same can be inferred from other consortiums which comprising of a technical partner (Fintech) as well as a financial partner (traditional financial institution).

The award of digital banking licenses will usher a new chapter for Malaysia’s financial industry to respond to the changing needs of the society, particularly the younger demographic who are financially and technology savvy. It will also create greater exuberance in the financial services space through the involvement and innovation of fast-moving Fintech start-ups to penetrate the banking industry and engage head-on with traditional banks. Malaysia’s Fintech ecosystem has its best days ahead of it!

Having read our CIO’s piece on “The Physical Impossibility of Death in The Mind of Someone Living by Damien Hirst” (The Kapitalist Monthly 003, December 2021), the ignorance and exuberance of the establishment led me, Joe. C down the rabbit hole. From the hilarious Cattelan’s banana taped to a wall ($120,000) to the downright ridiculous Rabbit Sculpture ($91 million), Hirst’s work is not the only embodiment of excesses in the financial world. Although his work personifies greed, and to a certain extent vulgarity, Hirst did help to shack up a dreary and complacent arts scene. But what do all these got to do with digital banking and Fintech you say? (Yes, you did).

Enter “The Emerald Isle Collection”

A limited 7-piece custom made whisky set released by The Craft Irish Whiskey Co. in collaboration with the legendary artist jeweller Fabergé. Just a single set will set you back $3 million. To many (JoeNatasha included), one must be insane to spend that much on what essentially is wood infused ethanol and some sculptures. Some even ridicule these buyers, albeit with tinge of envy. For the uninitiated, Irish whisky industry almost went bust during temperance movements in Ireland and Prohibition in the US. This essentially means 30 years old1 Irish aqua vitae are rare. This coupled with legacy of Fabergé Imperial eggs in Russia conjures scarcity mindset amongst collectors. In laymen terms, many do not understand why the collaborative product is valued as such.

Which brings us to the impact these “neobanks” has on the Financial Services industry. Most would say that it is difficult to compete against traditional banks (hence, why these digital banks are referred to as “challenger banks”). These new-kids-on-the-block, if ever, could only make a dent, but never disrupt the big boys. We see it differently!

We think the establishment of these digital banks could add dynamism to the Financial Services, an industry often painted as ‘boring’ and lacks innovation. It’s time that the industry has someone like Damien Hirst – adventurous, opportunistic and non-conformist. The diversity of players would make the industry more vibrant, and if the traditional banks could harness the synergistic value of collaboration with these challenger banks – just like The Emerald Isle Collection – the result could be greater than the sum of its parts.

1 Years of maturation means the youngest batch of whisky in the bottle. A 30 years old bottle essentially means the youngest Irish Pot still in the bottle is 30 Years of Age; potentially containing older and more matured Irish pot still.

Strategic Alliances between Banks and Fintech for Digital Innovation

In times of rapid technology adoption, firms within the financial services sector increasingly form alliances with start-up companies to satisfy customer demand and needs for new innovative products and growing market dynamics. Technology-enabled innovation challenges traditional business models of incumbent institutions and require them to adapt swiftly to the needs of the digital age.

However, Fintech companies also face difficulties, such as meeting regulatory requirements and winning the trust of customers. To overcome this challenge and to reap synergistic values, banks and Fintech companies are increasingly pooling their strengths in alliances. Going through the digital banks that are established in the market, we noted that banks are interested to partner with Fintech companies as they would want to benefit from the rapid innovation without necessarily being involved in its department, while Fintech companies demand resources and know-how to scale in the highly regulated financial sector.

Once believed that the Fintech companies would be a disruptor to the financial sector, it has rather led to the co-existence of start-ups and established firms and as a result, to ‘bank-Fintech’ alliances. The advantages offered by Fintech companies have been identified in the area of customer experience, whereas those of banks lie mainly in the back-office processing and meeting regulatory standards. Consequently, Fintech companies have established an image representing innovation and exploration, whereas banks represent continuity and seniority. Such form of alliance is not new in other sectors. For example, in the beer industry, the increasing number of microbreweries has broadened the beer market and created new business opportunities and customer groups. Thus, many large players have reconsidered their product portfolio or actively approached microbreweries.

We have seen in the market where there are different type of bank-Fintech alliances. The relationship between the two parties can either be 1) vertical – between buyer and seller, 2) horizontal – between competitors, or a combination of both. Furthermore, alliances can be additive or complementary. Given the differences in skill and knowledge, which has been identified as “ingredients” for alliances, banks and Fintech companies appear to be well-suited candidates for complementary alliances.

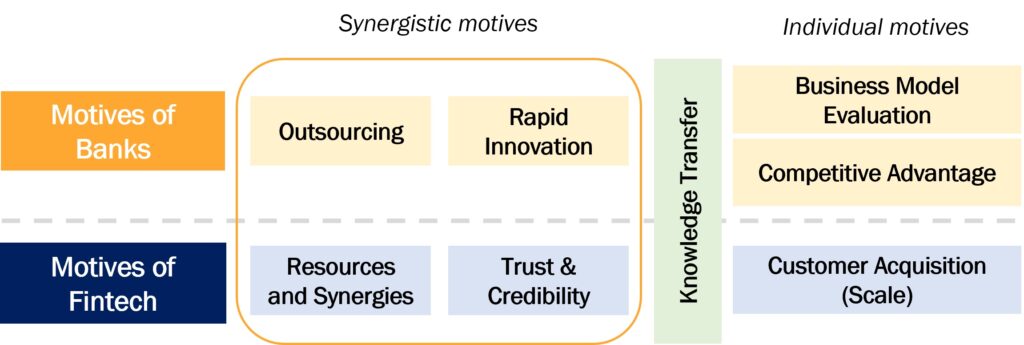

A study conducted by Frankfurt School of Finance & Management identified 19 banks that announced alliances with 29 Fintech companies. Their C-suite executives were approached for an interview to further understand the motives of the bank-Fintech alliances. The result can be summarised as below:

Systemisation of Motives

Most motives within the bank and Fintech groups are unique and distinct, with only one factor overlapping between the two groups i.e. Learning. However, if you compare the bank and Fintech motives side by side, it shows how most of the motives to engage one another are complimentary in nature.

Complimentary motives are considered as beneficial for both sides of an alliance and as supportive for fostering digital innovation. For example, the banks’ motives of allying with Fintech companies to encourage innovation and speed up the introduction of financial technology harmonises well with the Fintech companies’ need for resources (banking license). In addition, banks aim to outsource certain activities, such as developing digital applications for standard services (peer-to-peer money transfer apps, gamification of traditional banking services, etc.), implementing new regulatory rules and servicing niche customer groups, and Fintech companies can assist to provide the outreach for these activities. This can lead to “coopetition” as banks and Fintech companies cooperate and compete healthily at the same time (Bengtsson & Kock, 2000).

We can also see where banks and Fintech have their own agenda in pursuing an alliance together. To improve banks’ own competitive advantage, some banks use Fintech for innovative (often highly customised solutions) application programming or specialised tasks. Other banks use alliances with Fintech as an opportunity to evolve their business model. Certain Fintech start-ups pursue alliances with banks primarily to promote their products based on the banks’ trust and credibility.

‘Coopetition’, Not Competition

As mentioned above, the relationship between banks and Fintech companies are complementary in nature for the most part. A key motivating factor for Fintech companies, beyond acquiring the banks’ licenses and branding trust, is their desire for banks to act as guarantors to the customer. This is important for Fintech companies because finance is a sensitive issue for customers who do not want to entrust their money to small and unknown providers without regulatory oversight.

Looking deeper at the bank-Fintech alliances, we noted that the maturity of the Fintech companies plays a part in the relationship. Banks are more likely to invest in fast-growing Fintech companies for small equity as they can mould these companies to their needs while engage in product-related collaborations with more mature or larger Fintech companies. Hence, smaller Fintech companies are more likely to have a longer relationship with banks as larger Fintech companies are exposed to higher substitution risk if their product suite is not strong enough.

Digital Banking Case Study (1/2)

Partnership

- Olivia is an Artificial Intelligence (AI) Fintech.

- Helps Nubank develop personalised financial intelligence recommendations for its clients.

- It helps users plan their expenses and save money.

- An American platform specialising in creating automated and personalised proactive conversations between banks and clients.

- This platform allows for millions of conversations at the same time as well as handling of two-way communications seamlessly.

- A Brazilian firm that supports e-commerce transactions using the country’s PIX instant payments platform.

- Spin Pay worked with more than 220 retailers from various sector.

- Spin Pay moved R$1 trillion in just 6 months of operation.

- A software consultancy firm behind the Clojure programming language and Datomic database.

- This is used to further enhance Nubank as a digital bank.

- Easynvest is a leading D2C digital investment platform in Brazil. The brand is renamed to “NuInvest”.

- The platform has an existing 1.6 million users.

- This investment allows Nubank’s customers to have access to a complete range of investments including government bonds.

- A Brazilian consultancy company that specialises in start-ups and their digital products since 2009.

- It also has talents in developing and deploying workflow methodologies.

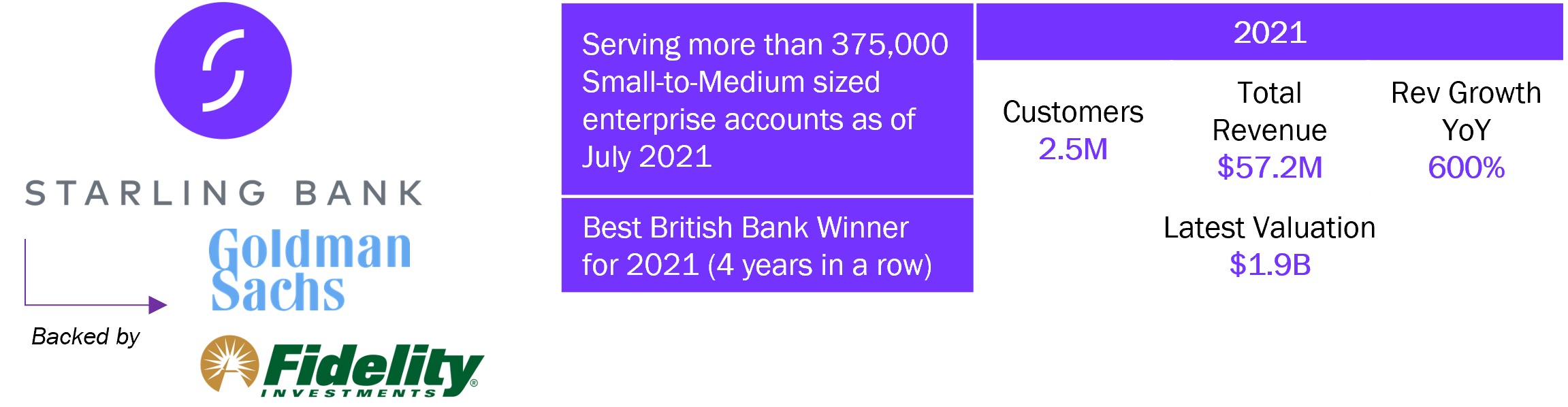

Digital Banking Case Study (2/2)

Partnership

- First acquisition of Starling Bank

- £50 million cash and share deal

- The company focuses on providing mortgages to professional and semi-professional buy-to-let landlords, only via mortgage adviser distribution channels.

- As of 26 July 2021, it has originated £2.3 billion mortgages and experienced zero credit losses.

- £1.75 billion of mortgages under management

- The company aims to provide lending to customers such as the self-employed who finds it hard to borrow from high street banks.

- It is one of the first to launch a fixed 40-year fixed rate mortgage.

- In 2021, Starling Bank bought £1 billion mortgage book from the company.

- In 2022, Starling Bank and Barclays Bank are both bidding to purchase the remaining mortgage business. The transaction is still on-going as at to date.

Complementing the Disruptor: Fintech Start-Ups Bringing Value to Digital Banking

On 31 December 2020, Bank Negara Malaysia has issued a framework for digital banking applicants to adhere to in their bid to secure the digital banking license. In the spirit of making banking accessible, digital banking license applicants would need to demonstrate a commitment in driving financial inclusion. This means the applicants would need to provide services that ensure quality access and responsible usage of financial services to underserved and hard-to-reach segments that may be unserved, which includes retail as well as micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs).

As the successful Malaysian digital banking license recipients are expected to be announced soon, let’s examine how this could impact the average consumers and Fintech start-ups.

Will Digital Banks Disrupt Fintech Start-Ups?

One of the key challenges that traditional banks face is determining the creditworthiness of an applicant. To minimise the default risk, traditional banks create a stringent credit approval process. Presently, the decision to lend by banks are influenced by information submitted by applicants and their credit score sourced from credit reporting agencies such as CTOS and Credit Bureau Malaysia.

What happens if the information submitted by applicants are accurate but not current? Case in point – say an applicant applies for a loan right before being fired from a stable job. The credit risk increases but the banks do not know until the applicant misses loan payments. New information will only be captured in the system as and when an applicant uses formal forms of financial services or public services. The new information pulled from these sources and complemented by information extracted from manual submission by the applicants could present some gaps that could be exploited.

This is where new Fintech start-ups that provide niche solutions can bring value to digital banks and complement traditional banking services. Pod, a Fintech start-up, currently partners Bank Islam in developing an alternative credit scoring model through its app. Through the partnership, both Pod and Bank Islam will explore solutions for underserved customers such as gig workers. With the pandemic and growing gig economy, alternative credit scores will have a demand and it serves as a bridge for digital banks to access to new customers in untapped markets.

Additionally, there are also Fintech start-ups that complements digital banking by creating new products that target previously unbanked customers such as earned wage access (EWA) to the masses. EWA enables employees to withdraw their earnings on demand instead of waiting for payday at the end of the month. EWA start-ups such as Payd helps people who have difficulties to make ends meet and live paycheck to paycheck by giving them access to earned wage at their fingertips. This deters them from borrowing from predatory lenders such as loan sharks and help in times of emergency expenses.

So how does EWA complement digital banking? EWA are often administered without disrupting an organisation’s payroll process. The credit risk falls on to the employer instead of the employee. Digital banks can tap into new SME customers and their employees through a partnership with EWA start-ups. The digital banks can also tap into more meaningful data in terms of demand of microcredit, spending habits and cross-selling of products in underserved markets, true to the spirit of financial inclusion.

Digital Banking to Drive the Financial Inclusion Agenda

Even before the pandemic, digital banking business models were gaining steam. News and headlines of banks trying to create new customer interfaces, streamlining customer journeys, and modernizing middle and back offices were often published. When the pandemic hit, the pace for digitalization and adoption of digital banking by customers sped up tenfold out of necessity driven by the unprecedented calamity.

As the traditional banking sector adopts technology, it will face tougher competition from digital banks, Fintech start-ups and decentralized finance (DeFi). To grow, traditional banks may adopt a mergers and acquisition strategy (M&A) which would see many Fintech start-ups being acquired to compete with digital banking. Time will tell where the fight will go. Either way, financial inclusion will be at the centre as the successful digital banking recipients strive to prove that they are able to back their promises to Bank Negara Malaysia.

Start-Ups Leading the Charge for Financial Inclusion

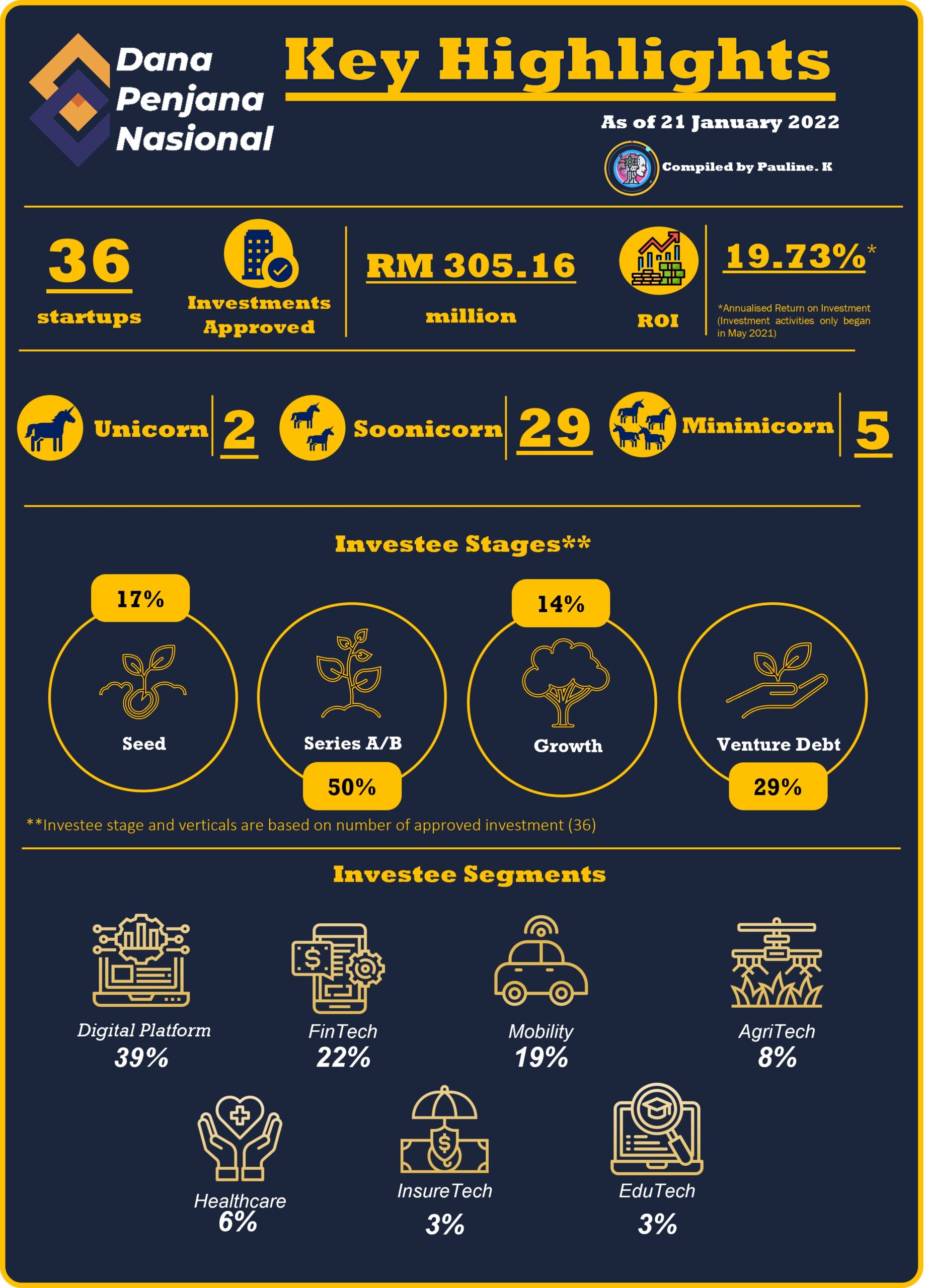

- Pod

Pod is a start-up that bridges between the financially underserved and financial institutions. The start-up leverages AI and machine learning to build alternate credit scores that enable gig workers to access credit from financial institutions. Established in Q1 2019, Pod started as a microsaving tool to help youth in Malaysia and Southeast-Asia save towards their financial goals. Dana Penjana Nasional’s The Hive Southeast Asia Fund has invested in Pod’s Seed funding round.

- Payd

![]()

Established in late 2020, Payd is a platform that provides instant access for workers to receive their paycheck in advance via withdrawing a portion of their earned salary between paydays. The company aims to assist low-income workers who have limited access to financing via earned wage access (“EWA”). Dana Penjana Nasional’s The Hive Southeast Asia Fund has invested in Payd’s Seed funding round.

| DISCLOSURES AND DISCLAIMER |

This Newsletter is strictly informational and is issued Penjana Kapital Sdn Bhd (“PKSB”) on the basis that it is only for the information of the particular person to whom it was provided. This document may not be copied, reproduced, distributed or published by any recipient for any purpose unless Penjana Kapital Sdn Bhd’s prior written consent is obtained. This newsletter has been prepared for information purposes only and is not intended as an offer to sell or a solicitation to buy any securities, and/or any other product in Public or Private markets. Penjana Kapital Sdn Bhd is not making any recommendation to buy any securities or other product and the information provided should not be taken as investment advice.

It has been prepared without regard to the individual financial circumstances and objectives of persons who receive it. Penjana Kapital Sdn Bhd has no obligation to update its opinion or the information in this newsletter and Penjana Kapital Sdn Bhd recommends that you independently evaluate particular investments and strategies and seek the advice of a financial adviser prior to entering into any transaction. The appropriateness of a particular investment or strategy will depend on your individual circumstances and objectives. The information herein was obtained or derived from sources that Penjana Kapital Sdn Bhd believes are reliable, but while all reasonable care has been taken to ensure that stated facts are accurate and opinions fair and reasonable, we do not represent that it is accurate or complete and it should not be relied upon as such. All opinions and estimates included in this newsletter constitute our views as of this date and are subject to change without notice.

Penjana Kapital Sdn Bhd is not acting as your advisor and does not owe any fiduciary duties to you in connection with this newsletter and no reliance may be placed on Penjana Kapital Sdn Bhd for advice or recommendations of any sort. Nothing in this newsletter shall constitute legal, accounting or tax advice, or a representation that any transaction or investment is appropriate for you taking into account your investment objectives, financial situation and particular needs, or otherwise constitutes any such advice to you. Penjana Kapital Sdn Bhd makes no representations or warranties, express or implied, with respect to the accuracy of the information or fitness for any particular purpose and does not accept any liability (including but not limited to any direct, indirect or consequential losses, loss of profits and damages) for any use you or your advisors make of the contents of this newsletter or for any loss that may arise from the use of this newsletter or reliance by any person upon such information or opinions provided in the newsletter. This newsletter has been prepared by the analysts of Penjana Kapital Sdn Bhd. Facts and views presented in this newsletter may not reflect the views of or information known to other business units within Penjana Kapital Sdn Bhd. This information herein is not intended to constitute “research” as it is defined by applicable laws. This newsletter is not directed to or intended for distribution to or use by any person or entity who is a citizen or resident of or located in any locality, state, country or other jurisdiction where such distribution, publication, availability or use would be contrary to law or regulation. The information provided in this document has been obtained or derived from sources believed to be reliable. Penjana Kapital Sdn Bhd does not guarantee its accuracy or completeness and does not assume any liability for any loss that may result from the reliance by any person upon any such information or opinion. Such information or opinions are subject to change without notice, are for general information only and is not intended as an offer to sell or a recommendation/ solicitation to buy any securities, foreign exchange or other product.