THE venture capital (VC) industry is one of the reasons why the United States has created many world-class technology based companies. Funding for start-ups has also helped other economies, including Taiwan, South Korea and Japan, create technology giants.

THE venture capital (VC) industry is one of the reasons why the United States has created many world-class technology based companies.

THE venture capital (VC) industry is one of the reasons why the United States has created many world-class technology based companies.

Funding for start-ups has also helped other economies, including Taiwan, South Korea and Japan, create technology giants.

In more recent times, Indonesian start-ups seem to be getting a lot of funding from an active VC scene there. Based on data by Crunchbase, Indonesia recorded US$8.7bil (RM38.3bil) and US$4.3bil (RM19bil) in VC funding in 2021 and 2022, respectively.

While VCs do exist in Malaysia, as well as the fact that over the years, the Malaysian government has spent billions of ringgit in VC funding via Malaysia Venture Capital Management (Mavcap) and other initiatives, market players still lament about lack of VC funding.

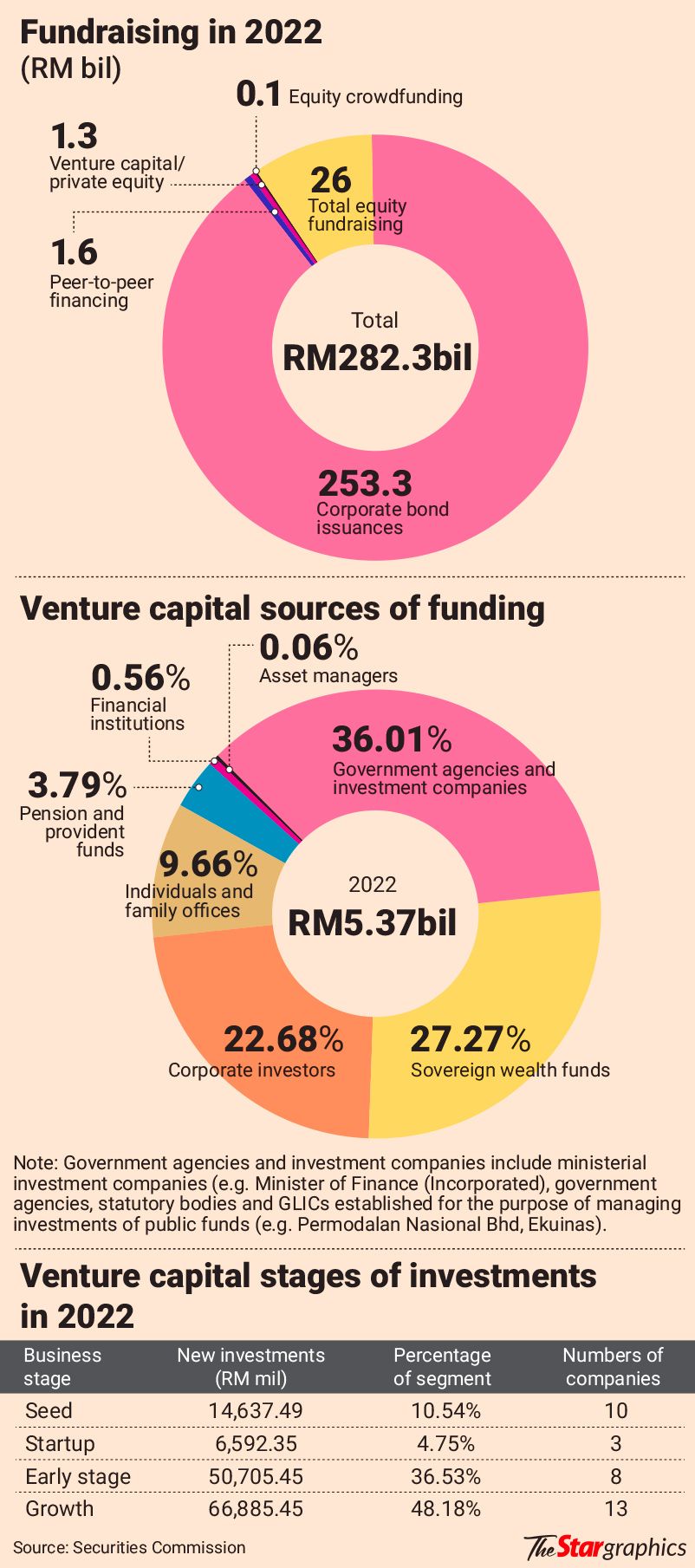

Another problem is that the VC monies in Malaysia come significantly from government agencies and related investment companies, with less than a quarter of the funding coming from corporate investors.

This is concerning because the local VC scene continues to depend on the government’s hand-holding, even after four decades since the inception of the domestic VC industry.

The “formal” VC industry in Malaysia began in 1984 with the establishment of Malaysian Ventures Bhd. And over the years, the government’s role in the VC industry has multiplied in different forms.

For example, Mavcap has built a fund size of over RM2bil and generated revenue of over RM10bil through its portfolio companies.

Set up in 2001, Mavcap is Malaysia’s largest VC fund under the purview of the Finance Ministry and the Science, Technology and Innovation Ministry.

The firm has also invested in over 15 start-ups which went on to become unicorn companies with a valuation of US$1bil (RM4.4bil), including Grab, Carsome, Bukalapak, Carousell and Airwallex.

Another example is Cradle Fund, a Finance Ministry-owned VC firm that has supported over 1000 Malaysian technology-based companies to date.

These include MyTeksi, which is now known as super-app Grab, listed on Nasdaq.

Apart from VC, the government has been instrumental in facilitating other alternative fundraising options in Malaysia.

In 2002, the government established Malaysia Debt Ventures Bhd (MDV) to provide customised financing facilities to develop the information and communications technology sector.

To date, MDV has disbursed over RM13bil to over 1,000 companies.

Despite the efforts taken over these years, it is still generally perceived that Malaysia does not have an active VC industry.

There has not been a strong buy-in from the private sector, although admittedly, it has been improving in recent years.

According to the Securities Commission (SC), government agencies and related investment companies are the biggest source of VC funding, making up of 36.01% in 2022.

Critics often point to the fact that insufficient VC funding in Malaysia resulted in some companies like Grab “leaving” Malaysia to meet its funding needs.

It is noteworthy that Grab moved its headquarters to Singapore in 2014, about two years after it was founded in Malaysia.

But this is not to say that VC monies are not flowing into Malaysian startups.

According to the SC, the total committed VC funds under management in Malaysia as at end-2022 was RM5.37bil, slightly higher than 2021’s RM5.18bil.

VC investments in 2022 concentrated on the growth stage (48.18%), followed by early stage (36.53%) and seed (10.54%) opportunities. In total, 34 VC deals were recorded last year.

Nevertheless, in seeking to address the dearth of money flowing into the local VC industry, Budget 2023 proposed for government-linked investment companies (GLICs) such as the Employees Provident Fund and Khazanah Nasional to invest up to RM1.5bil into highly innovative start-ups in Malaysia.

It is learnt that the institutions plan to invest in VC funds that have the expertise and experience in providing investments to startups.

The money from the two GLICs will not be in early stage investing, but more likely in Series B investments, which generally refer to a second round of funding for a firm that has hit certain milestones and past the initial startup stage.

Another notable effort by the government to resuscitate the local VC scene is Penjana Kapital Sdn Bhd, which was incorporated in July 2020.

Penjana Kapital administers and facilitates the deployment of the Dana Penjana Nasional, a matching fund-of-funds programme where the government will match, on a 1:1 basis, funds raised by the VC fund managers from foreign and private local investors.

The government had pledged RM600mil to be invested under the programme.

Together with the monies raised from the private sector, the proceeds will then be disbursed via VC firms across four different VC stages, namely, seed; Series A & B; growth; and venture debt.

Speaking with StarBizWeek, Penjana Kapital chief executive officer Taufiq Iskandar agrees that funding gap continues to be a critical issue to be solved in Malaysia.

He also points out that government and government-backed agencies have contributed, on average, about 75% of committed capital in the VC space.

Looking forward, Taufiq says the VC ecosystem can only be sustainable if the private sector steps in to replace the role of the government.

But, for that to happen, there needs to be a nudge from the government. Penjana Kapital is one such nudge.

“We crowd-in private capital to invest alongside the government in productive, but high-risk investments.

“Malaysia is not short of funds. If you look at the SC’s annual report, we have more than RM100bil in liquidity available in the market in the form of cash and deposits.

“These funds can be used for productive investments including in the VC space, but they are trapped in the balance sheet of corporates, family offices and others,” Taufiq says.

Splashing the cash

As pointed out by Taufiq, Malaysia also has other fundraising avenues for early stage companies such as equity crowdfunding (ECF) and peer-to-peer (P2P) lending.

Based on the SC’s data, about RM1.6bil in proceeds were fundraised in 2022 by P2P financing and about RM100mil were raised via ECF.

In comparison, a total of RM1.3bil were raised through VC and private equity (PE).

It is noteworthy that the total alternative fundraising in Malaysia – VC, PE, ECF and P2P – touched RM3bil in 2022, growing by 23.6% from the previous year.

Since 2018, the total alternative fundraising has grown by 44.6% per annum, driven by ECF and P2P fundraising.

When compared between PE and VC, the local PE scene has a better traction.

In 2022, the total committed funds in the PE industry stood at RM10.71bil, which is double the committed VC funds.

Interestingly, corporate investors are the largest source of funds, representing 33% of the commitments.

COPE Private Equity managing partner Datuk Azam Azman says that Malaysia has plenty of good companies worthy of PE investments.

“This is why we can see Singapore-based PE funds investing in Malaysia-based companies. It is not true that Malaysia lacks good companies, you just need to know how to look for them,” he says.

Azam, who has about two decades of experience in the regional PE scene, however notes that there are not many Malaysia-based PE firms.

This, hence, limits the options for alternative fundraising by Malaysian companies.

Azam applauds the government’s continued intervention in supporting the PE and VC ecosystem, calling it a “booster”.

“But, we also need more investors to the PE firms from the private sector. One area that we should focus on is the family offices.

“The prominence of family offices have grown regionally, but not so much in Malaysia. Family offices are key investors for PE firms, which would then benefit local companies,” he says.

A family office is a privately held company that handles investment management and wealth management for a wealthy family.

Going forward, as Malaysia works towards to achieving its goal to create five unicorns by 2025, the need for alternative fundraising avenues has become more pressing.

A unicorn is a privately owned startup company with a value of over US$1bil (RM4.4bil). Used car marketplace Carsome is Malaysia’s first-ever unicorn.

Penjana Kapital’s Taufiq says that the appetite for alternative fundraising has been on the rise, including in the VC space.

“Under our first round of fundraising that was completed, we raised RM1.3bil, higher than our target of RM1.2bil.

“Dana Penjana contributed RM600mil in matching grants, while the rest was contributed by the private sector. After our matching, some investors had topped up their commitment, which enabled us to surpass our target,” he says.

Challenges abound

Taufiq acknowledges that there has not been adequate funding for scale-up growth companies in Malaysia.

“Our upcoming second round of fundraising will be growth-focused in terms of stage of financing.

“We will be looking at companies related to energy transition, climate transition such as agrofood and technologies of the future such as blockchain and artificial intelligence,” he adds.

The increased focus on growth-stage companies is understandable, given that there are more funds available in the market for early-stage companies as compared to growth-stage companies.

Taufiq recalled that Malaysia almost “lost” Carsome to Singapore during the Series D fundraising.

“Singapore came in with the offer that Carsome must relocate its headquarters to the country, like it did with Grab.

“When it comes to scale-up or growth stage, the minimum investment amount is US$50mil (RM220.1mil) and how could government agencies like us compete? This is why we need the private sector to come in,” he says.

Mavcap CEO Shahril Anas tells StarBizWeek that there there is a lack of funds for Series C, growth funds until initial public offering.

Shahril says that it is crucial for the VC sector to focus more on developing the latter growth funding stages to support promising local startups and entrepreneurs and ensure that they do not feel the need to turn to other markets outside of Malaysia to seek funding.

“The need for a follow through on the VC ecosystem is essential to ensure that VCs have the opportunity to expand.

“We cannot afford to operate in the same landscape while expecting progress in the VC sector,” he says.

In order to help bridge the funding gap, Shahril notes that VC players in the country should work together collaboratively to provide a healthy funding runway for startups and expand support to the growth stage of the market.

“Through collaboration and partnerships amongst investors, there is a need to build more accessible growth funds to support our start-ups to flourish in Malaysia,” he says.

Meanwhile, serial entrepreneur Ganesh Kumar Bangah says that Malaysia lacks “intelligent capital” that can help start-ups.

“The actual understanding on the needs of start-ups is still limited among private investors.

“We need more intelligent capital in the market, which means capital that comes together with investors’ ability to evaluate a start-up’s business model and provide a helping hand to connect these start-ups with potential clients and opportunities,” he says.Ganesh suggests the government to introduce incentives to encourage corporates flushed with cash to invest in start-ups.

An example of the incentive would be low-interest financing to invest in start-ups, he says.

“Penjana Kapital should also provide matching grants directly to corporates, instead of just going through VC funds.

“When corporates invest directly in start-ups, they can have strategic positions and incorporate the start-ups in their network of supply chains and clientele,” according to Ganesh.

Last month, Khazanah Nasional unveiled the Future Malaysia Programme, which aims to support the local start-up ecosystem of entrepreneurs, start-ups, venture capital and corporate venture programmes through collaborations with domestic and international partners.

Under the programme, the sovereign wealth fund will deploy an initial amount of approximately RM180mil.

Separately, Khazanah has also announced its partnership with venture capital funds, namely Gobi Partners and 500 Global.

While VC funding plays an important in the nurturing of local start-up venture, one cannot deny the fact that VC investments are naturally highly risky.

Start-up failure rate ranges between 50% and 95% in developing countries such as Malaysia, according to a research paper by Universiti Sains Malaysia’s School of Management professors Daisy Mui Hung Kee, Yusmani Mohd Yusoff and Sabai Khin.

This is concerning, especially if the taxpayers’ monies are involved.

The Retirement Fund Inc (KWAP), which invests in PE as part of its private market portfolio, agrees that private market deals provides relatively unstructured risk to the portfolio.

“Nevertheless, over the course of time it has shown that the private market has been able to provide a higher return over the public market,” KWAP CEO Nik Amlizan Mohamed says in an email response.

Nik Amlizan explains that the higher risk associated with private market is first managed through Kwap’s Strategic Asset Allocation, where the total exposure to private market is capped at around 20% of Kwap’s total asset under management.

The private market risk is also managed through portfolio diversification, whereby the private market exposure is done in both direct and indirect investments.

divider

Looking ahead, Nik Amlizan says that the importance of the VC space cannot be ignored as it is a driver of future growth and innovation that can provide very attractive risk-adjusted returns.

“Therefore, KWAP has been making investments into the VC space globally since 2016 and will continue to do so with priority given to Malaysia, in order to support and develop the relatively younger VC ecosystem domestically.

“In this regard, KWAP is currently working on a catalytic programme with the aim to invest more in the VC and technology companies that have a Malaysia-centric strategy,” she says.

While the government is relentlessly encouraging the growth of local innovative companies or start-ups, some quarters have also raised concerns about the transparency of investments and how relevant agencies are operated.

In the case of Mavcap, there are criticisms that Mavcap’s funding has become too small to make meaningful investments and that it is difficult to directly engage Mavcap with proposals.

In response, Shahril says that Mavcap’s proven track record “speaks for itself”.

“Over the years, Mavcap has facilitated a total of RM2.2bil in funds which have been made accessible to the Malaysian start-up ecosystem.

“Today, we are enroute to record a total fair value of RM1bil for our portfolio of investments,” he says.

Shahril also says that the firm’s ILHAMAVCAP series helped to spur the VC scene, whereby successful entrepreneurs are invited to share their experience to the community.

“MAVCAPLACE, a co-working place at our office every Friday to support local startup to facilitate their business and to network; our engagements at start-up or small and medium enterprise events to provide knowledge and access to funds; demo days for startups to pitch their businesses for funding; as well as engaging with universities on developing startup and VC talent,” he adds.

(Web source: https://www.thestar.com.my/business/business-news/2023/04/08/long-way-to-go-for-countrys-vc-scene)